This blog post is sponsored by Tellason. Read about how we run this site here.

Since White Oak’s Closure, Tellason has Redefined What it Means to Be an American-Made Brand

As the birthplace of riveted overalls, San Francisco occupies a very special place in the history of denim workwear. Start a denim brand in the Bay Area and you’re inviting comparisons with Levi’s, the brand that helped make American-made workwear iconic.

Tellason founders Pete Searson and Tony Patella don’t shy away from these comparisons, but they are careful to distinguish between the legacy of San Franciscan workwear and the current realities of the global denim industry. To put it mildly, “American denim” doesn’t carry the same cachet it once did.

The legacy brands long ago began to stray from the formula that put American workwear on the map. Once the very definition of the well-made American-made product, blue jeans have become a consumer product as ubiquitous as bread and milk. Produced in huge quantities in inexpensive labour markets, America’s most iconic product has not been made how it used to be or where it used to be for a very long time.

Pete and Tony don’t place the blame for this at the feet of the legacy brands. Brands like Levi’s, Lee, and Wrangler have merely responded to pressures placed on them by mass-market consumers, who care more, says Tony, about “price than provenance”.

Still, there is a subset of consumers who still care deeply about how and where the products they purchase are made. In 2008, when Tellason was starting to take shape, well-made workwear was in the midst of a renaissance. Young brands like Tellason gambled on the emergence of a new kind of consumer who shared their passion for local and high-quality manufacturing.

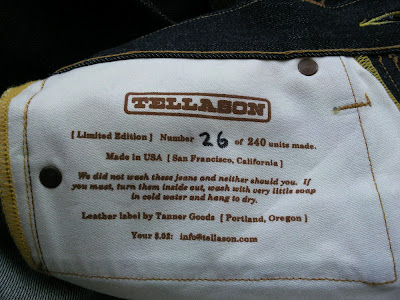

For Tellason, the old formulas are the best. You take some of the best available fabrics and you carefully cut and sew them into timelessly stylish and dependable pieces—and you do it close to home. Tony Patella and Pete Searson have followed this formula since they founded Tellason (a portmanteau of their last names) in Tony’s garage in San Francisco in 2008.

This made-in-America formula had been one of the keys to Tellason’s success, and Pete and Tony weren’t about to mess with a winning recipe. But circumstances beyond their control would force their hand.

Cone of Fame: Cone Mills and the Birth of Tellason

Pete and Tony had known each other for nearly two decades when they went into business together. When they decided to start a denim brand in 2008, the first phone call that they placed was to the San Francisco offices of Cone Mills.

Tony had an existing relationship with the legendary American mill. He had worked closely with them in the ‘90s, when he had helped Cliff Abbey start Sutter’s Denim. Some of Tony’s contacts in the Greensboro office (including the credit manager) were still with the company, so the path was paved. The mill offered Pete and Tony extremely generous terms that would not have been on the table had they just walked in off the street.

They also got their pick of Cone’s extensive range of denims. Most fledgling brands would have access to only a limited number of fabrics, but Pete and Tony got full and immediate access. For their first pairs, they chose the now-legendary 13.25 oz. #1968 selvedge denim.

The now-closed Seattle-based Tellason retailer, Blackbird, posted the images below in April 2009 (source) when they took stock of some of the very first Tellason jeans, made from the #1968 selvedge denim.

After two years with this American selvedge as the backbone of their production, they had a strong enough relationship with Cone Mills that they could look at producing a range of proprietary denims.

It’s hard to overstate just how important this is for young brands that are laying the foundation for a long stay in the industry. A proprietary denim isn’t just about getting exactly what you want. It’s also about a predictable and dependable supply of raw materials. Young brands who find initial success often learn this lesson too late. After selling out of their first run, they may have to return to the market with what is essentially a different product.

Pete and Tony wanted to avoid this pitfall, but, as a small-batch denim brand, they weren’t yet large enough to meet the production minimums for proprietary fabrics. Luckily, they had impressed the folks at Cone Mills, who were confident that the brand would be around for long enough to use whatever yardage they produced.

Cone Mills allowed Tellason to order well below their usual minimums. They saw Pete and Tony’s young brand as a bankable commodity. In a way, Cone invested in Tellason’s future. Tony says that Tellason repaid this display of trust by “never leaving Cone Mills hanging with excess fabric”.

Their first proprietary Cone denim was a 12.5 oz. selvedge with a high sulfur content (to limit crocking). The denim is also light on starch, which makes it an easy-wearing entry point for customers who are experiencing raw denim for the first time.

Hot on the heels of this popular denim came their 14.75 oz. selvedge, which had a much higher indigo content. After this, they upped the weight, developing a rigid 16.5 oz. selvedge with less indigo saturation—a combination that gives the fabric its legendary high-contrast fade potential.

These proprietary fabrics would see Tellason through its youth and adolescence. By 2017, Tellason was an established brand with a cadre of passionate customers and stable of popular pieces. Something big was coming down the pipe, though.

End of an Era: The White Oak Falls

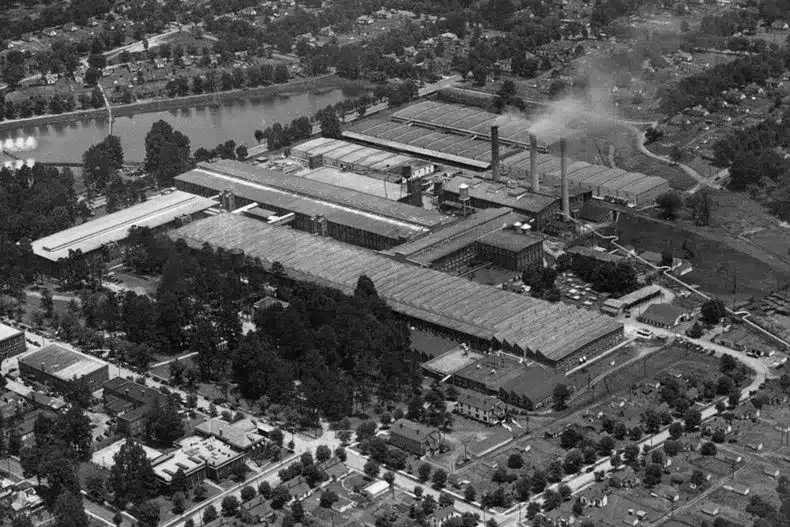

For fans of American heritage menswear, the closure of the iconic White Oak Cone Mills plant seemed to fall out of the clear blue sky. The very definition of a sure thing, the Greensboro plant had been churning out rolls of American-made selvedge for well over a century when it closed its doors on the last day of 2017.

Denims produced in the White Oak plant were the backbone of America’s most iconic product, the Levi’s 501XX. Beginning with the so-called ‘Golden Handshake’ deal in 1915, the workwear manufacturer and the textile mill combined to help turn the five-pocket jean from a humble piece of workwear into a fashion staple.

The International Textile Group, Cone Mills’ parent company since 2004, cited “changes in market demand” in their decision to close the plant. Some of the mill’s largest and longest-lasting customers had moved their production into inexpensive labor markets. By 2017, Tellason was the mill’s fourth-largest customer.

This was a reflection of Tellason’s growth, but also of the decline of American manufacturing. Tony still remembers receiving the call on October 17th of 2017, which came shortly before the public announcement. The representative asked if Tony was sitting down. Tony told him that he already knew what the call was about. He had been expecting it since the rep had told him where Tellason ranked among the mill’s customers.

The White Oak plant was a sprawling complex covering more than a million square feet. Tellason’s selvedge was all produced in a small corner of the plant, where 40 of the old Draper looms were still chattering away, bouncing up and down on the famously springy hardwood floors. If things had been running smoothly in Greensboro, a small-batch denim brand like Tellason wouldn’t have cracked the top 10 on Cone’s client list.

The rot that led White Oak to fall was a symptom of wider problems in the American textile industry. Passionate selvedge consumers and the brands that preferred premium made-in-America denims could only keep the plant on life support for so long before the wider issues caught up with them.

Cone Mills told Pete and Tony that, before they closed at the end of the year, they would ship them as much selvedge denim as they could handle (and pay for, of course). They placed a massive Tellason order—so large that it was shipped via rail instead of the usual route via the interstate highways. The rolls would see them through about 18 months of production.

Looking to the future, when the rolls of their proprietary selvedge would inevitably run out, they turned their gaze to the west—across the Pacific Ocean to Japan.

Pacific Rim: Tellason Looks to Japan

Pete and Tony knew that the vacuum left behind in the American selvedge scene by the closure of the White Oak plant would likely be filled by Japanese mills, who had arguably been producing the world’s best selvedge denims for decades. There were other mills producing competitive denims in Europe, but, with the White Oak plant closing, the legacy of American-made selvedge had essentially come to an end.

There were rumblings that American mills would pick up where White Oak left off, but Pete and Tony didn’t just need selvedge denim. They needed the kind of weaving expertise and experience that the technicians at Cone Mills had been able to provide, and they couldn’t wait for a new mill to get up to speed. They decided to move their denim production to Japan.

There were a number of factors that went into this decision. Proximity was a big one. The rolls of selvedge that had come via road or rail during Tellason’s Cone years would now be arriving on cargo ships. The Japanese mills were a straight shot across the Pacific (just 28 days of sailing on a container ship). The European mills had a much longer route through the Panama canal.

Tony created a short list of six Japanese mills. He cut this list in half after learning that three of the mills were already doing business with American selvedge brands. Pete and Tony had good relationships with these brands, and they didn’t want to step on their toes. This left three mills, with one at the top of that list: Fukayama’s Kaihara Mills.

They had planned to spend a few months weighing their options, but a representative from Kaihara interrupted their deliberations with a well-timed phone call. He offered to help Pete and Tony recreate the proprietary denims that they had developed with Cone. They agreed to let the mill show them what they could do.

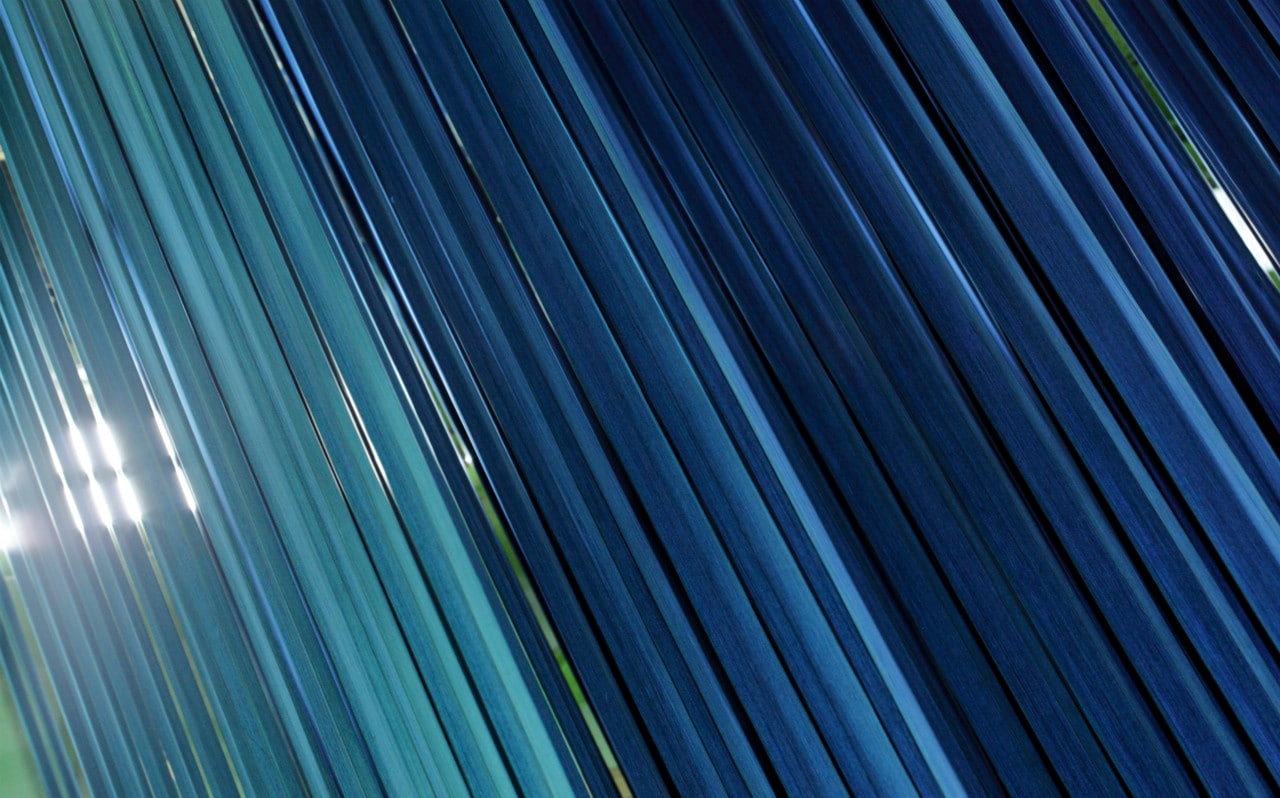

They knew that Kaihara would be a reliable supplier. The mill has been producing denim in Japan since 1970 (they were the first to introduce rope-dyeing), and they started using vintage Toyoda looms for some of their premium selvedge denims in 1994. They wanted Tellason’s business, but they had a laundry list of denim brands as clients. They didn’t need Pete and Tony’s orders to keep the lights on. They were a sure thing.

They began the process of creating a new proprietary denim that would look, feel, and fade like the denims they had first developed with Cone in 2010. They wanted the transition between the two suppliers to be as seamless as possible, so that, in the store, pairs made from the Kaihara denim could sit side by side with the Cone Mills pairs without any immediately recognizable differences between the pairs.

They provided Kaihara with the spec sheets and samples of the fabrics in both its raw form and in faded pairs. Cone Mills wouldn’t provide their complete recipe, but Kaihara demonstrated their technical mastery.

After four months of trial and error, they were able to reverse engineer the recipe, with yarns and indigo concentrations identical in nearly every way. Tony visited the facilities in Japan, and they handed him a sample of the 14.75 oz. selvedge. It was, says Tony, “remarkable”.

It was the start of a new era for Tellason—one that would see the brand preaching the virtues of the nearly unbeatable one-two punch of Japanese selvedge and American manufacturing.

What Made in America Means to Tellason

Tellason’s denims might be milled in Japan, but they can still call themselves a made-in-America selvedge brand without blushing. They source all of their thread, hardware, leather patches, and their heavy-duty pocket bags from American suppliers, and their manufacturing partner is located in San Francisco—only a few minutes’ drive from the Tellason offices.

If Pete and Tony have questions about the raw materials, it’s a long flight across the Pacific to get hands on with the dyers and weavers in Kaihara. Most questions, though, are related to how the garments are assembled and finished, and Pete and Tony are fanatical about the details (stitches per inch, thread quality, etc.).

Because it’s such a short trip to the San Francisco sewing factory, they actually have these conversations about the smaller details, and they are more likely to raise issues if they notice even the smallest dip in construction quality.

By keeping manufacturing close to home, Tellason is putting their money where their mouth is. They pay a hefty premium to have their products made on American shores, but these costs are worthwhile for them. They’re not (and never want to be) a mass-market denim brand, and this means they don’t have the same kind of mass-market pressures as the department store brands. Their customers prefer to pay slightly more for a premium product, and this is what they deliver.

They don’t see themselves as an on-trend fashion brand, and they don’t even try to be all things to all people. Comfortable in their niche, they are as dependable as they come. They don’t rock the boat with radically new styles or cuts.

Indeed, as Tony says, Tellason isn’t remotely interested in innovation. All of Tellason’s jeans are variations on the same theme (all of them based on their iconic John Graham Mellor fit), and they haven’t changed at all since their first pairs.

Tellason does things differently by doing things always and in all ways the same. Crucially, they do these things as close to home as possible. For Pete and Tony, for their customers, and for us, this is what it means to be Made in America, and it makes all the difference.

To find out more about Tellason, you can read our profile of the brand, see our list of their five most iconic products, or head straight to Tellason’s website.

Keeping Up with Tellason

Each week, Tellason names one of its products the Item of the Week. In a short video, the founders dive into the story behind the product, discussing how it came to be part of the Tellason family, its pre-Tellason history, and how it can be styled.

Each Item of the Week is discounted by 20%, so it’s definitely worthwhile to get notifications from Tellason each time a new Item of the Week is announced.

Check out the current Item of the Week here and sign up to receive them weekly.