Discover the Ways Design Influences How Your Jeans Look, How They Feel, and How They Wear and Fade

You probably know there’s such a thing as ‘designer jeans.’ But have you ever thought about how misleading that term could be; indicating that only designer jeans are designed?

Of course, that’s not true.

All jeans are designed. Whether your jeans are made from kittens eyelashes and embellished with rhinestones, or they’re a vintage non-name brand you found at your local thrift store; they’ve been designed by a designer.

Visit our buying guides before your next purchase. We guide you to the best raw selvedge jeans, denim jackets, heavy flannels, T-shirts, denim shirts, and more.

The design influences all aspects of the garment; how it looks, how it feels on the body, how it wears and fades. The design also differentiates makers. And when it comes to designing jeans, nothing can be left to chance.

Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works,” Steve Jobs famously said.

That’s just as true in our world of slubs and stitches as it is in Apple’s world of bits and bytes. But what does it take to design a pair of jeans? That’s the question this first episode of the ‘how jeans are made’ series answers.

There are three parts in the series about how jeans are made:

- Design and development (this post)

- Cut and sew

- Garment finishing

What’s In A Job Title?

As the ‘how denim is made’ series proves, denim is a complex fabric. It lives and changes with you. There are almost endless ways the cotton, spinning, dyeing, weaving and finishing processes can be combined to create unique fabrics. That means it’s a challenging one to work with for designers.

The responsibilities of a fashion designer are most often sourcing and design. Once those tasks are completed, the reins are handed over to a developer who—under the supervision of the designer—turns the design into actual garments.

A denim designer holds both roles. She’s both the designer and the developer. She needs to understand how the particular combination of production steps for the fabric work with the design she has in mind. How will the denim fade? How will the fading match the thread colour and thickness, the stitch count, and all the other details?

You can’t design denim garments without knowing the fabric you’ll use,” says Christina Agtzidou, who has been working with denim design and development since 2000. “The final garment will be defined by your selection of fabric, design details, the way it’s stitched, as well as treatment and finishing. This is what’s actually design when it comes to denim,” she says.

Where To Start the Design Process?

There’s no ‘right way’ to approach denim design. Different designers have different routines and methods. With 35 years under her belt, Christine Rucci has worked with influencers such as Adriano Goldschmied and François Girbaud, as well as brands likes Double RL.

She calls her design process “the 5 F’s of denim”; Fabric, Fit, Finish, Factory and Fashion. Other designers and developers I’ve talked to have different approaches, but their design processes all include the following three stages:

- Research

- Technical sketch

- Treatment design

Now, let’s take a closer look at each of these stages to find out how they impact the garments you’re selling to your customers. It’s probably more complex than you ever imagined.

Research: You Can’t Be Everything To Everyone

The first stage in designing a pair of jeans is to do research about where to have them made and what kind of materials to use. This means you need to get familiar with your target audience and their needs.

You have to define a ‘persona.’ What kind of fits does the consumer like? How old is he? What kind of garments does he wear his jeans with? What’s his budget? Based on the answers to questions like these, the denim designer gets an idea about where to start her sourcing.

Sourcing Fabrics and Production

These days, mills are offering almost endless selections of fabrics. Focusing on the outcome sets limits and helps denim designers select the right fabrics. They need to keep an eye on the features of the fabric and what’s possible to do with it in the stitching and laundry processes. And because not all fabrics work with all patterns, selecting fabrics is the first step. So what do denim designers look for?

I check the weight, width, the weave, the indigo colour and the grain line (the warp),” says Christine Rucci.

Usually, a trial wash is made with the selected fabric to ensure that the cast and optics turn out as expected. Denim designers might also base their decision on how sustainable a specific fabric is, and for instance, go with options made with recycled yarns.

Another important aspect to consider when selecting fabrics is whether the same fabric can be used for more than one style. Do you really need both a 12 oz. indigo blue denim and similar 13 oz. one?

The goal for forward-thinking denim designers is to do more with less and achieve multiple looks with just one fabric. Christine Rucci calls this approach “fashion flexible”:

I opt to go narrow in qualities and deep in finishing. This helps from a logistic and financial standpoint,” she argues.

A key benefit of this approach is that it minimises production complexities. It also enables designers to get better denim at a lower cost. And it helps with pre-booking of fabrics.

From an environmental perspective, using fewer fabrics can help limit the waste mills produce when they develop new ones. While the fabric is the key ingredient, designers also need to think about what kind of trim will match the style of the jeans they’re making, as well as how the garment fades.

The sourcing stage is also where denim designers select suppliers and factories. Especially when starting with new suppliers, it’s important to know the limitations of the facilities. What kind of machinery do they have? Which operations are manual and which are automated? What’s the seam allowance, which you need to know to make a pattern? How to they set pockets? What kind of pattern templates do they have? (A custom template costs around $10k.) Do the accessory machines work with the selected trim? And so on.

All the decisions a denim designer makes in the research and sourcing stage have a profound impact on the jeans that end up on the shelves in retail.

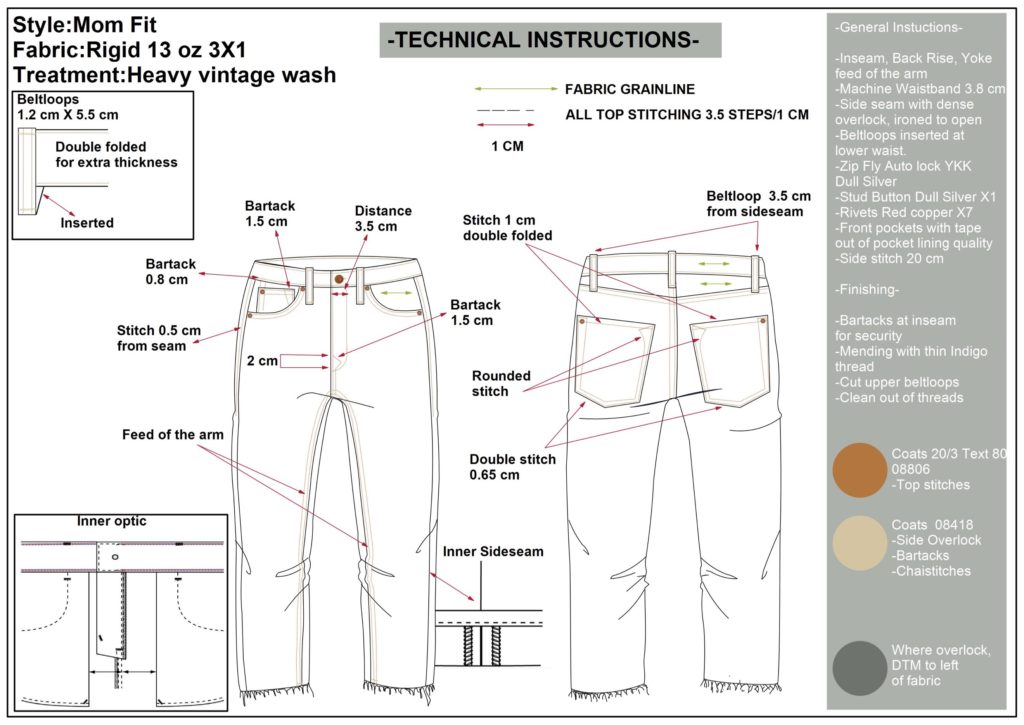

Technical Sketch: What You Design Is What You Get

Twisted seams, issues with tearing, bad fits, ‘flat’ washes, characterless garments. These are common problems for denim designers when they’re developing denim garments. While it would be easy to blame the factory or the R&D department, it usually comes down to the quality of the designer’s technical sketch, which is the second stage in designing a pair of jeans.

It’s paramount that the sketch precisely explains what you want the garment to look like,” Christina Agtzidou says. “And you should understand how the fabric behaves to ensure production runs smoothly.”

The most important element of the sketch is the pattern, which the anatomy of the jeans and determines how they fit. A normal pair of jeans is made from roughly 20 different cuts. Details like the yoke are important. This is the section on the back of jeans that’s traditionally in a V-shape. Together with the curved seat and the shorter front rise; the yoke gives jeans their signature figure-hugging fit. But the yoke is just one aspect of the pattern.

Pattern and Fitting

A patternmaker develops the pattern, usually together with the designer. It’s made with special software on computers, although some small-scale makers still make patterns by hand. In any case, the research from the first stage gives an idea about what kind of fit to go for.

I look at people and ask myself who my customer is,” says Christine Rucci, “what’s their body type, what do they do in their jeans?”

Then there are the characteristics of the fabric, the grain line in particular. Self-taught jeans maker, Paul Kruize, points out that with traditional jeans patterns, the outseam is straight.

With other trousers, both the inseam as well as the outseam are curved to make the fit. But with jeans, only the inseam is curved. This prescribes a different approach to making the pattern. For selvedge denim, the outseam must be cut straight on the grain, which means the designer needs to create the leg shape and fit from the inseam. And, especially for stretch denim, the designer needs to pay close attention to skewing.

Christine Rucci also educates that designers must also consider the waistband, and that they must pay attention and the mid-thigh measurement (6″ below the crotch) and the front and back rises. “If you do not get these measurements right, they can affect the entire fit,” she warns. That’s why a shrinkage test and likely subsequent adjustments are musts.

Christina Agtzidou mentions that designers must also observe how the fabric behaves when worn; this information will radically affect the measurements and the fit.

The weight, construction, treatment, elasticity, stretch recovery, softness and how it relaxes after wearing will all influence the fit,” she explains.

Surprisingly, she reveals that for each fabric, you (might) need a pattern. Sometimes the pattern even needs adjustments as a result of the laundry treatments.

Even when a pattern has been made for one fabric, if several treatments are applied, each one of them can make it react differently. A rinse wash will not definitely behave the same as a super bleached treatment,” the Greek denim designer explains.

Once the pattern is ready, it’s plotted onto paper or cardboard and laid out onto the fabric. In large-scale production setups, multiple layers of fabric are cut at the same time using a special saw.

The next step in the technical sketch is stitching.

Stitching

Any denimhead worth his salt knows there’s a distinct aesthetic difference between the puckering of a lockstitched hem and that of a chain-stitched hem. Different stitching techniques give completely different outcomes. That’s why the technical sketch for a denim garment must contain every and all the different kinds of stitches that the designer wants to use.

Clarifying the stitching methods and ways of reinforcement help the maker understand your idea of the final garment,” the Christina Agtzidou advises.

Let’s look at some of the most important stitching steps for blue jeans that a denim designer has in her toolbox.

Leg Seams

Traditionally, jeans are made with so-called ‘busted outseams.’ This is what gives the two bits of fabric on the inside of the outseam, which for selvedge denim are left as they are and for wide-loomed denim needs overlocking. The inseams are usually either top-stitched or flat-felled. While flat-felled seams are the most durable, the busted outseams and the top-stitched inseams are the most original, which means they’re usually found on replica designs.

Bartacks

Bartacks are a series of stitches that have traditionally been used as a reinforcement. Nowadays, they can also work as a design feature. Most notably, Lee have made their X-bartack a design signature. Historically, bartacks are known to have replaced rivets on back pockets in the first part of the 20th century.

Chain Stitching

Denim enthusiasts have come to love chain stitching on the hem of their jeans as it creates the desirable roping effect. The cause is the ‘feed differential’ caused by the ‘folder,’ the static ‘presser foot’ and the ‘feed dogs’ of the chain stitching machine.

As the folder rolls the fabric together, the feed dogs move the bottom layer of fabric while the top layer is wedged between the presser foot and the folder. This creates a slight skew that results in puckering once the jeans are washed. With the renewed attention on chain-stitched hems, it’s not only heritage denim designs that feature them; the stitching has become common practice on most quality jeans.

But it’s not only at the leg openings designers use chain stitching. In addition to being easy to manage in production, as chain stitching only needs one thread spool, it’s also more flexible than a lockstitch. That means it’s often used in places that shrink and stretch, such as the waistband.

Thread

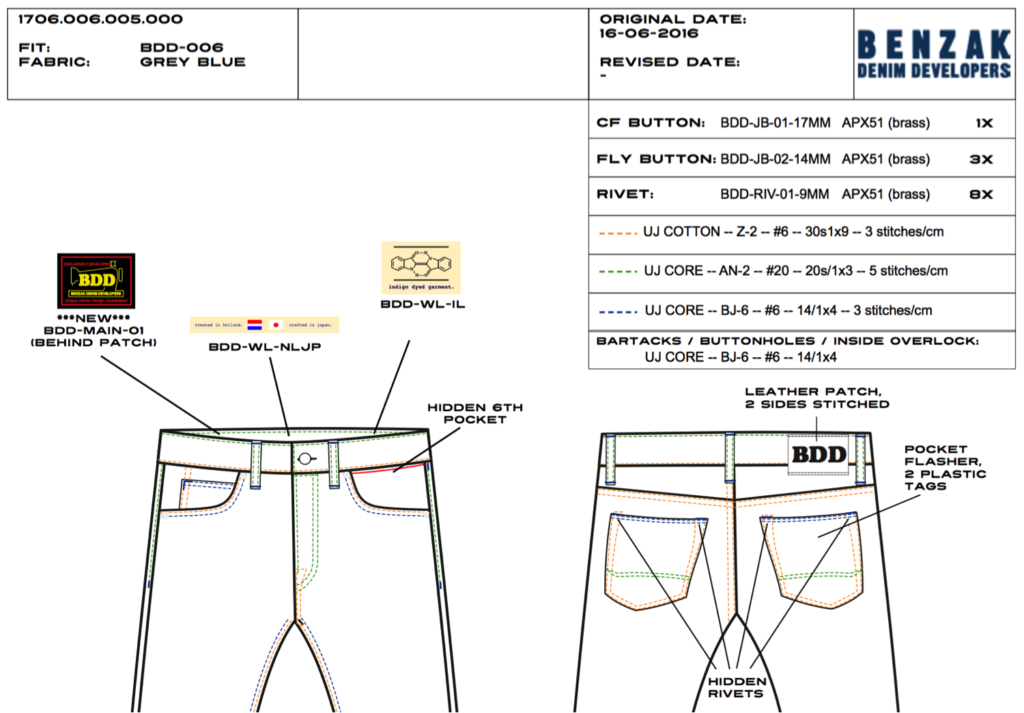

In addition to the different sewing methods, the thread itself also gives denim designers room to play with different colours, rows of stitching, thread thickness as well as stitch count.

The most classic thread colours are yellow and tobacco, which match the colour of the copper rivets. Tonal blue or black thread, on the other hand, are often found on more contemporary designs. Since jeans were originally made as workwear, they were sewn with thick and durable thread.

The top-stitched and felled seams give visible rows of stitching. For five-pocket design, it’s common to have one or two rows. For workwear designs, three rows are common. Denim designers also use different thread thicknesses and stitch counts to create unique and playful effects. Lennaert Nijgh uses two thicknesses, three colours and various stitch counts on his BDD jeans.

With almost endless opportunities regarding how the fit and the stitching of a pair of jeans can be made, the decisions a denim designer makes in the technical sketching stage can make or break the jeans. But it’s the treatment design that’s probably the most eye-catching.

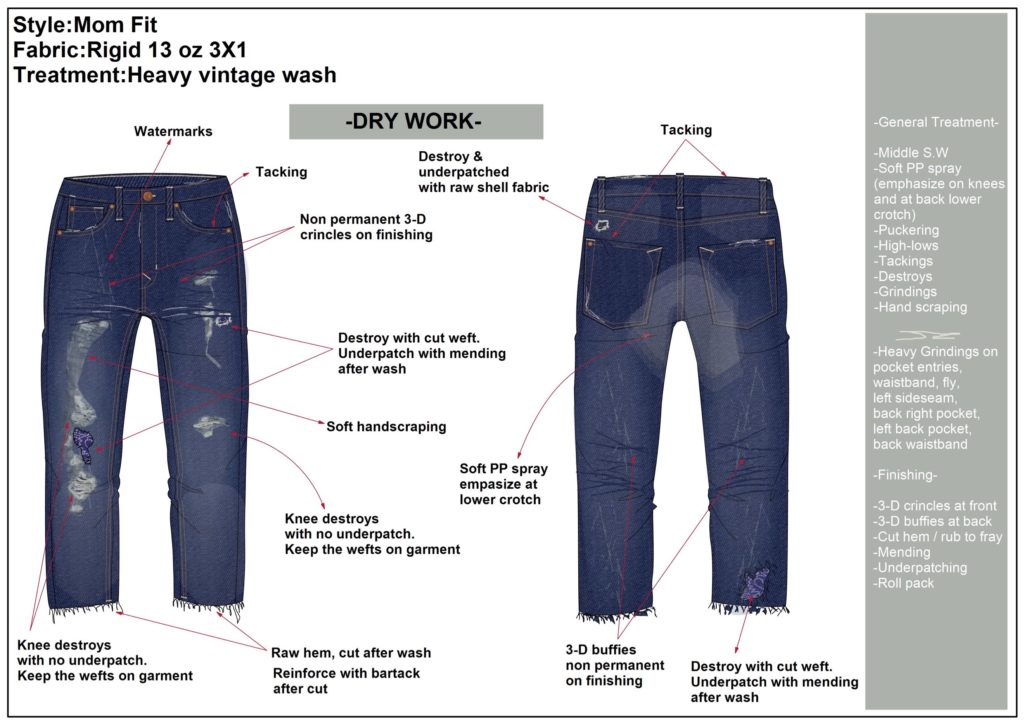

Treatment Design: Defining the Wash

The third stage in designing a pair of jeans is the treatment; the garment finishing. (Naturally, this stage is not relevant for raw denim jeans.) While this is part of the process is usually developed in collaboration with the R&D department of the laundry, the denim designer gets the best results by sketching out the character she wants to achieve.

What kind of destroyed effects should the jeans have? Where should fading agents such as PP spray be applied? What kind of hand-scraping should be used? What about grinded edges, whiskers, honeycombs and 3D effects? And how “washed down” should the jeans be?

The designer needs to consider this because treatments yield different results on different fabrics. And because not all fabrics can stand the same processes.

Still, the designer doesn’t need to make a complete ‘wash recipe.’ “You guide the laundry by drawing all the special features,” Christina Agtzidou explains. It is essentially a technical sketch for the washing process.

The treatment design will then be made on a sample, and based on that the final wash is developed. While designers usually find inspiration in vintage archives, with innovative treatment processes such as laser and ozone, laundries can go beyond ‘vintage’ looks to create new trends. This is something the denim designer can really use to her advantage.

“Mills have really stepped up in recent years and present a great array of finishes,” Christine Rucci observes.

It almost goes without saying that the treatment design process plays a crucial role in what the garment will end up looking like. And that concludes the first episode of the ‘how jeans are made’ series. In the next instalment, I’ll look more closely into how jeans are cut and sewn.

On the Hunt For Raw Selvedge Jeans?

Launched in 2011 by Thomas Stege Bojer as one of the first denim blogs, Denimhunters has become a trusted source of denim knowledge and buying guidance for readers around the world.

Our buying guides help you build a timeless and adaptable wardrobe of carefully crafted items that are made to last. Start your hunt here!