The Visual and Environmental Impacts of the Last Stage in Making Jeans

If you ask a denim fan what his favourite feature of jeans is, he’s probably going to talk about the way they fade. Jeans are unlike most garments in that regard; the more worn they look, the more we like them.

It’s not only enthusiasts who like jeans that have a lived-in look, most consumers do. In fact, even despite the resurgence in raw and unwashed denim, the faded look and soft touch of pre-washed jeans are still by far the most popular. While the denimhead prefers to create his own “wash,” most people are perfectly fine with taking a shortcut and buying jeans that are already washed and worn.

That’s one of the reasons why the sector of the denim industry that has seen most innovation over the past decades is the jeans laundering business. It’s the final production stage in the making of jeans; the procedures referred to as pre-distressing, laundering or—in industry speak—garment finishing, commonly known as ‘pre-washing.’ The result of this process is usually referred to as ‘washed’ jeans.

But what is pre-washing, how is it done, where does it come from, and what will it look like in the future? This third and last episode of the series about how jeans are made answers those questions.

The three parts in the series about how jeans are made are:

- Design and development

- Cut and sew

- Garment finishing (this post)

What Is Pre-Washing?

The starting point for any jean is raw and unwashed denim. That’s what all jeans are like when they leave the cutting and sewing stage. Essentially, you can start wearing the jeans without any further processing, which is what raw denim aficionados prefer to do.

The process of pre-washing covers a host of industrial garment finishing procedures that most jeans undergo. The aim is usually to replicate the look that raw denim jeans get with everyday wear and wash. It’s usually all about purposely ageing the garment.

Sometimes, though, the goal is to offer lighter and softer jeans, which is what Lennaert Nijgh of Benzak Denim Developers is going to do for the A/W17 season:

I do not include whiskers and such. The target audience is the guy who doesn’t always want to wear dry and rotate with something different. Pre-washing is not always about skipping the wear-in step.”

In any case, pre-washing is the third and optional stage in making jeans—one that is purely about how the jeans look, and not function.

The benefit of pre-washing is that the wearer gets jeans that look and feel lived-in, right of the store shelf. The reasons to choose pre-washed jeans are usually that they’re softer and thus more comfortable, but often it’s also a matter of personal preference and what’s in fashion.

The disadvantage of pre-washed jeans is that they sometimes don’t last as long as unwashed jeans. Alice Tonello of the famous developer of garment finishing technologies, Tonello, explains:

It’s obvious that a pre-washed jeans will not last as long as a raw one. That’s because raw denim has not been distressed and the fibres is still intact with starch and sizing as well.”

Even with non-abrasive pre-distressing, you’re effectively shaving off wear time. But, if you’re planning to only wear the jeans for a season or two, it might not be your biggest concern.

A much more global issue of washing and distressing jeans in factories is the environmental impact. Even the most sustainable jeans laundering methods require resources, including time, energy and water. And they produce waste. But more about that later.

So why is it that most jeans sold today are pre-washed? Back in the good ol’ days, before jeans transitioned into the world of fashion, they were all raw and unwashed. Workers wore jeans for their durability and practicality, not because of how they looked. It wouldn’t make sense at all to purposely distress your jeans when you wanted them to last as long as possible! That all started changing in the 1960s.

Why Most Jeans Are Pre-Washed Today

As I’ve discussed in the series about how history has shaped our jeans, jeans migrated from the US to Europe and Asia in the years following WWII.

Like many other commodities that provided US soldiers with the comfort and memory of home, jeans became a symbol of freedom and the American way of life. Quite unknowingly, the American GIs created what would become a denim craze that eventually changed fashion.

But back then, new jeans were hard to get in Europe and Asia. The first denim aficionados outside of the US generally had to wear whatever they could buy secondhand. When secondhand jeans became an established business during the 1950s, the jeans were washed for sanitary reasons. This meant that Europeans and Asians first came to know and love denim in its worn and washed state.

Local jeans makers and retailers also found it surprisingly difficult to sell new, unwashed jeans when they were first introduced in the mid-1960s. When I met the French denim innovator, Francois Girbaud during my research for Blue Blooded, he told me about some of his first experiences with raw denim. He helped open the Western House boutique in central Paris in 1964. The store sold blue jeans and authentic cowboy gear. “It was like little America in Paris,” he told me.

While Girbaud himself preferred unwashed jeans, his customers felt differently. They weren’t used to the rough, unwashed denim, and they began asking for jeans that looked and felt like the ones Girbaud had worn in himself. Many wouldn’t believe that a little wear and wash would naturally transform the jeans—a scenario anyone who’s tried selling raw denim probably recognises.

Based on requests from customers, Girbaud got the idea to start washing the jeans before he sold them. At first, he washed the jeans at a local launderette. He soon moved the washing to an industrial laundry. And he discovered it was a lucrative business; the washed jeans sold at double the price.

To accelerate the fading process, Girbaud experimented with rocks, sand and other abrading substances until he discovered pumice stone in a beauty store in Italy. That made him one of the first ever to stonewash jeans.

The same thing happened in Japan where the first domestic brands also started making jeans in the mid-1960s. Consumers wanted worn and wash jeans like the American secondhand ones they’d bought at the black market in Tokyo. Pioneering Japanese jeans brands like Big John began washing their jeans.

By the 1980s, jeans were not only stonewashed but also bleached, “acid-washed,” hand-scraped and chemically distressed in other ways. Let’s take a closer look at some of the most common “traditional” ways of pre-washing jeans.

The Traditional Methods of Pre-Washing Jeans

When we talk about pre-washed jeans and garment finishing, stonewashing is hard to get around. It was this pre-washing method that kickstarted the denim laundering industry, and it’s used in denim laundries all over the world to this day.

However, these days, things are a little more complicated. Most washes are created with a combination of several different pre-washing methods, which is known ‘recipes.’

It’s the endless combinations of fabric cast vs. chemicals vs. craftsmanship that can create so many different looks, all from the same blue jeans,” says denim designer, Klas Dalquist.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the most common traditional garment finishing methods used to fade and soften jeans.

Rinsing

A rinse is the simplest denim laundry process; the jeans are washed in water. The purpose is to soften the denim and give it that one-wash look.

Many Japanese brands sell their jeans rinsed, or one-washed, especially when they’re made from unsanforized denim, in which case the rinse shrinks down the jeans.

If the jeans are going through further washing steps, laundries also ‘desize’ the jeans—that is, remove the sizing agent (starch) to make the denim softer—before other treatments.

The rinsing process is also often one of the last steps in the laundry ‘recipe’ with the purpose of washing out and neutralising fading agents.

Stonewashing

Simply put, stonewashing is a laundry process where garments—in this case jeans—are washed with pumice stones. The stones are added to the laundry machine, and the rough surface of the stones abrades the fabric and wears off the indigo dye. The result is a softer touch and washed-down look.

Getting the right stones has not always been easy. Industry veteran, Panos Sofianos recalls how he had to tell a little white lie to his supplier back in the early 80s when he was working in his native Greece:

We needed a source for pumice stones. The best came from a volcanic island called Nisyros. The only supplier there refused to sell more than few kilograms to us because he could not believe we were really looking for material for industrially laundering jeans. We had to lie, saying that the pumice would be used for insulation in ovens.”

Hand Scraping

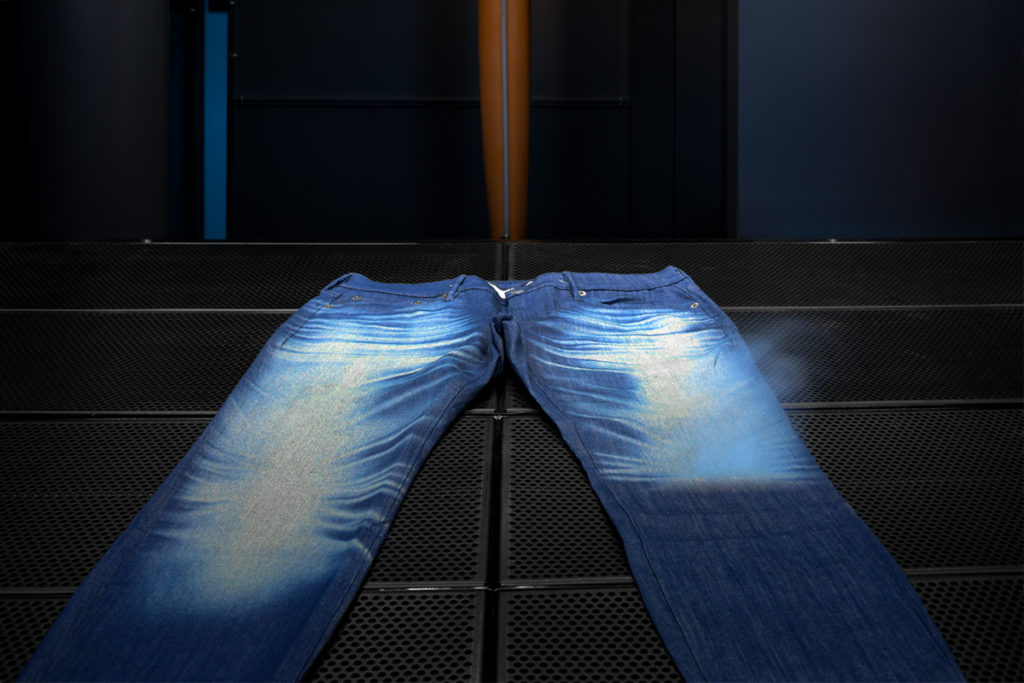

Hand scraping is a manual garment finishing process that is used to recreate whiskers and honeycombs, as well as general fading on the thighs and the seat area, which you normally get with natural wear and tear.

As the name suggests, the scraping is done by hand. And it’s labour-intensive. Trained craftsmen use sandpaper, sanding blocks and other sanding tools to abrade the denim and remove the colour. Sometimes, a mould with all the creases is used. This makes the process quicker, but more expensive as new moulds need to be created for every wash. Craftsmen may also use drills to distress the hems and pocket edges or to create nicks and cuts.

While it may look relatively easy, if you’ve ever tried hand scraping yourself, you know it’s not! What the jeans end up looking like in the end greatly depends on the skills and attention to detail of the craftsman. Hand scraping is also the finishing process that’s often used to create breaks and rips.

Sandblasting

Sandblasting is a garment finishing process where tiny sand grains are blasted onto the jeans under high pressure. It gives a result similar to hand scraping, but it’s faster and less physically exhausting to do. Industry veteran, Martin Schaefer, recalls his first encounter with the method:

I saw it first in 1986 in a French laundry. The raw jeans were lying on a table and the sand was blown onto the jeans. It’s a horribly dusty method, and the workers were wearing masks, but that wasn’t enough.”

Sandblasting has been harshly criticised as the procedure puts workers at severe risk of lung cancer and eventually death when it’s done without proper ventilation and the right safety equipment.

As Tony and Pete of Tellason write on their blog, “the use of sandblasting increased when the distressed denim trend took off in the 1990s.” The finishing method was banned in 2009 in Turkey when the government discovered that many denim workers were dying! The following year, 40 of the world’s biggest denim brands including, Levi Strauss & Co. and H&M, banned sandblasting to put an end the fatal approach.

Sandblasting is safe when it’s done under controlled circumstances with workers wearing the appropriate protection gear. The problem is that in most places where sandblasting was (and is) used, safety is neglected, to say the least.

Bleaching

As early as the late-1960s, laundries started experimenting with ways to create an overall washed-down look using chemical bleaching agents, such as chlorine. This garment finishing process dramatically brightens the colour of the jeans without abrasion.

Although the result is also an overall fade, bleaching is not comparable to stonewashing, argues denim designer, Stefano Aldighieri.

Bleaching is not an alternative to stonewashing. It can, however, accelerate the colour loss and thereby expedite the process.”

PP Spraying

Another common chemical used to fade jeans without abrasion is potassium permanganate, often abbreviated ‘PP.’ This liquid chlorine-free oxidising fading agent is used to recreating local fading, just like hand scraping.

PP is usually hand-sprayed onto certain areas of the garment, which is mounted on rubber dummies. It can also be applied by hand with a special glove or a paint brush, or even without any manual work using robots.

3D Shaping

The issue with industrially-made whiskers and honeycombs is that they often lack the 3D effect you get when you’ve created them with natural wear. 3D shaping aims to recreate just that.

This manual finishing process replicates the look denim gets when it’s moulded to your body. It’s used both before and after the local fading is done. And you can have both permanent and temporary 3D shaping.

This manual finishing process replicates the look denim gets when it’s moulded to your body. It’s used both before and after the local fading is done. And you can have both permanent and temporary 3D shaping.

The jeans are usually dipped in or sprayed with starch that makes the denim stiff. Then they’re fitted on a rubber dummy, and the legs are bent like if a person was squatting a little. Workers then manually crinkle the jeans in the places where whiskers and honeycombs would naturally appear. To set the crease in place, the jeans are then baked in a massive industrial oven.

New and More Sustainable Methods of Pre-Washing Jeans

Since it’s inception, the jeans laundering industry has constantly been exploring new and more effective ways to better replicate the authentic fading of naturally worn-in jeans. Since the early 2000s, the industry has been developing alternatives to conventional and high-impact garment finishing.

The objective to find lower impact and more sustainable methods is predominantly a result of media and governmental pressure, caused after horrific stories about how harmful the industry can be at its worst.

It’s also partly the result of growing public concern about climate change, which is nominally reflected in consumer demand for more sustainably made clothes. In a time where the effects of climate change have become everyday news, the environmental impact of this nice-to-have process of making jeans has caught public interest.

It’s also because jeans makers and laundries have realised that it’s good for them. In many cases, pre-washing sustainably is not only beneficial for the environment, it also saves the laundries expenses for water, energy, chemicals and labour. There has thus been a continuous search for ways to reduce water consumption, use fewer chemicals, and consume less energy for washing and finishing jeans.

The research has led to innovative technologies such as ozone treatments to replace stonewashing and rinsing, and laser to replace bleaching and sanding. Let’s take a closer look at some of these new pre-washing methods.

Ozone Washing

Ozone washing is a laundry technology that is used to “rinse” and fade jeans. Natural ozone gas is created by miniature thunderstorms in a closed-circuit environment and then injected into the laundry machine.

Ozone was initially use to clean the redeposition of indigo from the pockets and the weft. Today, it’s also used to remove indigo,” Stefano Aldighieri explains. “It still does use water, albeit in very small amounts.”

When injected into the laundry machine, the ozone gas has the same effect on denim as stonewashing, only it’s more environmentally sustainable. The main advantage of ozone is that process consumes much less water and has virtually no waste, compared to stonewashing.

Enzyme Washing

The enzyme washing technology gives jeans a washed-down and aged look as well as a soft touch. Using natural enzymes to brighten the jeans, the method is an eco-friendly alternative to stonewashing.

It’s also used on more delicate qualities,” explains denim designer, Christina Agtzidou. “I usually use stonewashing for rigid and comfort stretch denim. For stretch denim with polyester or Tencel, I use enzyme washing.”

NoStone

Tonello in Italy has been one of the world’s leading makers of laundry machines since the early 80s.

Together with Levi’s, they’ve recently developed a new alternative to stonewashing; their proprietary mechanical NoStone method. It replaces the pumice stones with abrasive metal plates that are attached to the drum of the machine.

The result is a wash that is identical stonewashing but with a much smaller environmental footprint.

Laser

In recent years, the use of laser technology has been growing rapidly. A laser beam is used to create virtually any wash pattern in a matter of seconds. No water or chemical are used in the process, and it also drastically reduces the amount of manual labour that is needed compared to hand scraping.

It’s an amazing technique that has developed insanely,” Klas Dalquist enthusiastically explains. “When I started working with it in Italy in the early 2000s, it looked horrible, so fake and very difficult to change. You would get one pattern of whiskers and then they had to re-program the computer for different sizes!”

Since then, the technology has developed immensely, and it’s been implemented in laundries across the globe. Here’s what it looks like in action.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nnGA4POAydE

The Other Side of the Coin

Looking at denim objectively, it’s not hard to see why most consumers prefer pre-washed jeans. Unwashed denim is stiff; especially when it’s rigid (that is, without stretch), it can be uncomfortable to wear.

On top of that, it takes months of wear, even years for some, to reach the desired worn-in look. For someone who wants a certain look today—while it’s in fashion—choosing jeans made with industrial washing and finishing techniques to replicate the natural wear and tear is a no-brainer.

Yet it seems many aren’t even aware of the consequences of the choice they’re making when they’re buying pre-washed jeans.

Andrew Olah said it best in Blue Blooded; “denim is a dirty industry.” That’s why it’s important to discuss and understand the garment finishing stage of how jeans are made, regardless of whether you like how it looks or not.

Like everything else that affects our precious and fragile environment, the consequences of garment finished have a global impact, not only to the local communities where factory-washed and distressed jeans are made.

It’s important to notice that I’m not out to point any fingers here! The goal of this article—like anything else you’ll find on Denimhunters—is to help consumers make more informed and conscious decisions when they’re buying denim and jeans.

That being said, I believe it’s crucial that consumers understand the impact of their choices of jeans. They need to know that paying just a bit more and buying a garment that is been treated with less water, fewer chemicals, which makes it less polluting, is the conscious choice.

Or we could all just buy raw denim.

Share

Hi Thomas!

could sanforized denim be considered as raw denim?

Thanks!