This entry is a must-know term from our Denim vocabulary. For more information about rope dyeing and slasher dyeing visit this entry.

Indigo is the colour that makes blue jeans blue.

The indigo colour originates from India. The name ‘indigo’ comes from the Greek word ‘indikón’—which became ‘indicum’ in Latin—and the original meaning was simply “a substance from India.”

Indigo is one of the oldest dyestuffs still in use today. In 2016, a 6000-year-old scrap of fabric dyed with indigo was found in Peru.

Visit our buying guides before your next purchase. We guide you to the best raw selvedge jeans, denim jackets, heavy flannels, T-shirts, denim shirts, and more.

The history of indigo

Today, indigo-dyed garments are an integral part of everyone’s wardrobe: we all wear blue jeans. It’s easy to forget that indigo used to be a rare commodity.

Only a few centuries back, this mysterious dyestuff was so exclusive that only royalty and the aristocracy could afford it. It was imported with great difficulty from far-off colonies, which earned indigo a status similar to that of tea, coffee, silk or even gold.

Archaeologists have traced the use of indigo back 6,000 years, which makes it one of the oldest dyestuffs still in use today. The oldest preserved indigo-dyed textile fragments in existence were unearthed in pyramids built during Ancient Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty. That means they’re as much as 4,500 years old.

Natural indigo

In South Asia, the indigo pigment has traditionally been extracted from dried leaves from the indigofera tinctoria plant—also known as ‘true indigo.’

This is what we call ‘natural indigo’ today.

The dye is extracted through fermentation; a series of biochemical reactions produce an indigo sludge that can be dried into blocks and then ground into powder.

Europe had its version of natural indigo made from woad, a plant with similar properties to indigofera tinctoria. The first woad-dyed textiles appeared in Europe in the 8th century BC; in other words in the early Iron Age. For more than a thousand years, woad dominated in Europe. But true indigo binds better to less absorbent fibres such as cotton, which made it the favoured alternative.

The exotic true indigo was seen as a serious threat. In what indigo historian Jenny Balfour-Paul calls the “woad war,” woad growers, merchants, and even entire nations fought against the invasion of true indigo as they (with good reason) feared to lose their livelihoods.

As late as the 18th century, using true indigo remained punishable by death in Germany and France. Nevertheless, true indigo eventually surpassed woad.

The final death blow to woad was the introduction of synthesised indigo.

Synthetic indigo

Indigo used to be ‘natural’ as it was made from plants. These days, however, almost all indigo is synthetic through chemical engineering.

The basic chemical structure of synthetic indigo was discovered in 1878 by the German chemist, Adolf von Baeyer. It was, in fact, the first synthesised dyestuff ever made, which won von Baeyer the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1905.

Working with Germany’s Badische Anilin- & Soda-Fabrik (BASF), he spent three decades, and more money than the company’s entire capital value, refining synthetic indigo.

The result, introduced as ‘Indigo Pure’ in 1897, was a phenomenal success, despite initial scepticism. By 1914, 95% of all natural indigo production had disappeared.

Today, almost all blue denim is dyed with synthetic indigo.

Natural indigo vs. synthetic indigo

Let’s take a look at the main differences between natural indigo and synthetic indigo.

Natural indigo is more expensive

Not surprisingly, the most significant difference between the two is that synthetic indigo is a lot cheaper than natural indigo.

The price of synthetic indigo usually varies between $1 to $5 per 100 grammes whereas the price of natural indigo ranges from $20 to $40 per 100 grammes. With different qualities and grades, prices may vary even more.

To get a better idea of what this means at the cost of an average pair of jeans, you need to multiply the price with the amount of indigo needed to dye the fabric blue. For instance, for a pair of 12 oz. denim jeans, you need roughly 25 grammes of indigo.

Natural indigo is inconsistent in colour

An explanation for the big price difference is found in the method of dye extraction and production, which makes natural indigo much less colour-stable and thus even more costly to use.

The natural dyestuff contains impurities, and not even the best producers can guarantee the level of consistency that modern denim manufacturers demand. Denim mills which use natural indigo will be challenged with obtaining shade consistency and production feasibility, which drives up costs.

Regarding visual differences, denim woven from yarn dyed with natural indigo has more colour variation, a distinctive green cast—which is the tone of the fabric—and it fades slowly. Contrarily, denim that is woven from yarn dyed with synthetic indigo has a more uniform colour, a red cast—at least when it is not mixed with sulfur—and it fades faster with higher contrast.

There’s no replacement for natural indigo when it comes to the colours it creates. But, in today’s market, it’s impossible to meet the demand.

Natural indigo is less sustainable in denim production

In a day and age where sustainability is a top priority for most denim makers, natural indigo doesn’t make much sense.

“Natural” doesn’t necessarily mean “good for the environment.” Natural dyes have several restrictions in terms of performance, quality consistency and application compared to the synthetic dyes.

First of all, for the supply chain to keep up with demand, the natural indigo growing industry would take up a considerable amount of the world’s arable land.

On top of that, natural Indigo has lower build-up properties and lower fixation rates compared to synthetic indigo. This means you need more dye. The lower fixation rate also means you need more water to wash off unfixed dye in the rinsing step.

And, if natural indigo is dyed with a conventional chemical reducing agent, the impact of the byproduct overshadows any advantage that might be claimed from the dye’s natural origin. The alternative of natural fermentation from organic waste can only be considered for craft works.

In the end, even though synthesised indigo is made from petroleum products, it’s the most eco-friendly of the two. At least when used in denim production.

Pre-reduced indigo: The more eco-friendly alternative

Both natural and synthetic indigo traditionally comes in powder. Synthetic powder indigo is cheap and readily available. But many makers now use ‘pre-reduced indigo,’ which cuts the use of reducing agent chemicals significantly for the mill. It’s an important step in the direction towards a more sustainable future for denim.

Producers are shifting towards pre-reduced indigo as it’s more consistent, there’s less hustle with it and, above all, it’s shade brilliance is superior. Powder indigo will likely eventually end up like natural indigo; a romanticised part of the past.

Pre-reduced indigo is a more environmentally-friendly alternative because the solubilisation of the dye, which is done by the dye maker, requires no or far lower concentrations of the reducing agent. Another way to use less indigo is to replace it with another colour.

Alternatives to 100% indigo dyeing

Not all denim is dyed with indigo only.

Denim makers have three ways to dye: with 100% indigo, a with mix of indigo and sulfur, and with 100% sulfur. The latter is what’s used for black and colour denim.

In the 1970s, when denim makers scaled for mass production, sulfur was introduced to replace (some of) the indigo baths to cut costs. These days, sulfur is often used to add so-called tops and bottoms on indigo-dyed yarn, which is one way to create the cast. However, you can control the cast without sulfur simply by changing the chemistry of the dye bath.

Dyeing with 100% indigo produces a characteristic red cast like the one known from the iconic denim that Cone made for Levi’s in the 50s and 60s.

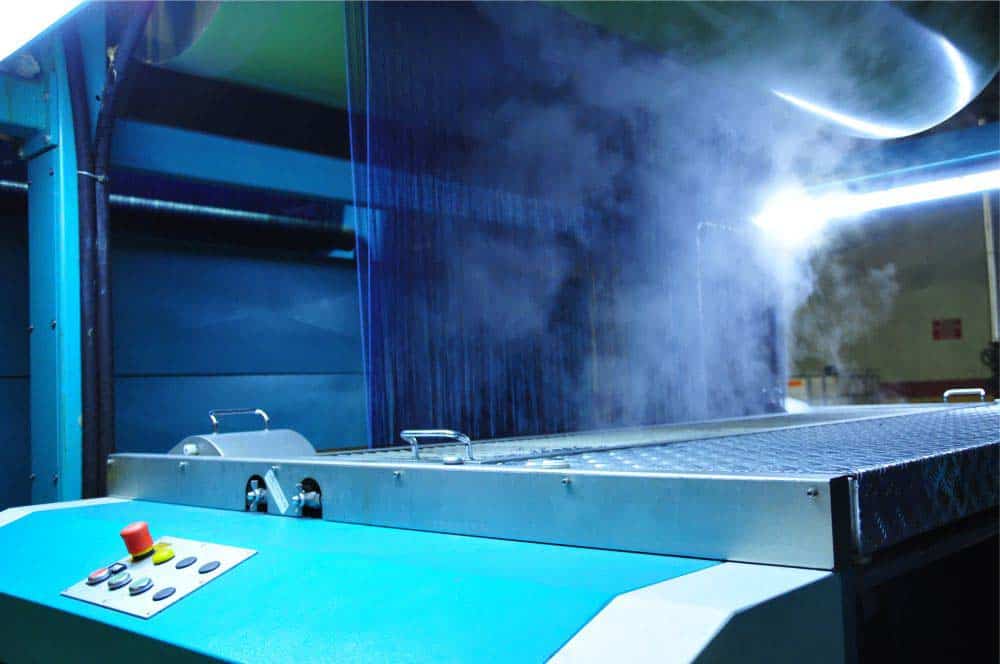

How to dye with indigo

Indigo is a vat dye. To get the dyestuff onto the yarn or the fabric, it’s solubilised in water with the help of a reducing agent.

When the yarn or fabric is pulled out of the dyeing vat, and gets in contact with the atmospheric oxygen, the oxidation process binds the colour molecules to the fibres of the yarn.

The reason denim fades is the modern dyeing process. It gives what’s known as a ‘ring dye effect.’ The colour doesn’t reach the core of the yarn. The dyestuff only binds externally. As the dye slowly wears and washes off, the undyed core appears.

When you buy a pair of raw denim jeans, there’s still have some starch left in fabric from the sizing process. Combined with the tightness of the weave, this is what gives raw denim its stiffness.

To learn more about the different dyeing methods that’re used to dye denim, go to the page about dyeing.