How History Has Shaped Our Jeans (Part 4)

It’s been ten years since what we now call heritage fashion started gaining wider public attention. Chunky flannel shirts, wild beards, heavy leather boots and, of course, raw denim jeans. It’s a stereotype that challenges our perception of masculinity when it’s overly curated and superficial, which is when it get the label ‘lumbersexual.’

While media put heritage fashion on its deathbed a couple of years ago—I’ve been guilty of that myself—heritage fashion isn’t going anywhere.

One of the main reasons is the style’s target audience: +25-year-old men that “found” themselves in heritage fashion. They’ll continue to live it; once a man’s found his style, he’s not likely to change it. As someone way smarter than me once said, “fashions fade, but style remains.”

It’s also because heritage fashion is not really about a particular look; it’s about putting quality over quantity. It’s a movement, really. Once you experience the difference between a product that is the real deal and one that is an imitation, you don’t want the latter anymore!

The seeds of the heritage fashion movement can be traced back to the decades following World War II when the Japanese built a cult around Americana and denim, which eventually led them to start making their own denim and jeans.

The four parts of the series about how history has shaped our jeans are:

- How Denim Went From Workwear to Fashion Statement

- How ‘Designer Jeans’ Broke Through the Mainstream

- How the Vintage Denim Scene Was Created

- Heritage Fashion and Japanese Denim (this episode)

It’s All About (Real) Attention to Detail

A key ingredient in the Japanese recipe for heritage fashion is attention to detail. It’s not just something they say because it’s hip, they actually put an incredible amount of attention to detail.

My good friend, Lennaert Nijgh has been making his Benzak Denim Developers jeans in Japan since 2013. While he was developing his first collection, he forgot to include the hidden rivets in one of his sketches. In most places, Lennaert would have ended up with jeans without hidden rivets. Not in Japan.

When I got the prototype back, the jeans had hidden rivets, accompanied with a little note saying ’you forget the hidden rivets’,” he argues in Blue Blooded. “That’s one of the reasons I produce in Japan.”

It’s that kind of attention to detail combined with an immense respect for traditions that has the Japanese came to be the undisputed world leaders of heritage fashion and Americana style. But we need to travel back to the middle of the last century to find out how they got there.

How Blue Jeans Came to Japan

Even before the start of the vintage denim craze, in the 1970s, the Japanese were stockpiling old jeans that no one else wanted. In fact, the Japanese fascination with American blue jeans dates all the way back to the late 1940s.

Like Europe, Japan’s first encounter with blue jeans came courtesy of occupying American soldiers. But up until recently, few people knew how it evolved from fascination with the cultural artefacts of the country’s former enemy to a world leading industry.

Thanks to the extensive research that W. David Marx did for his excellent book, Ametora—seriously, you need to read this one!—we now know about the companies and individuals that pioneered the Japanese denim culture.

During the American occupation of Japan in the years after the war, it was more or less impossible to get your hands on a new pair of jeans due to import regulations. The only place you could get new jeans was at the PX offices at the American military bases. It was easier to buy secondhand jeans, though.

Early adopters in Tokyo got their jeans from stores in the former black market, Ameyoko, in the Ueno district. Marx found out that the stores got their supply from so-called ‘pan-pan girls’ (i.e. prostitutes) who were paid in garments rather than cash by their American customers.

When import regulations were lifted in the 1950s, the Japanese could for the first time buy original new Levi’s and Lee jeans. They were expensive, and retailers soon started requesting cheaper domestically-made jeans. By the early 1960s, jeans were in such demand that a handful of local garment makers were racing to capture the enormous opportunity in the market.

Like today, many of the first Japanese-made jeans would come out of Kojima in the Okayama prefecture.

The First Japanese-Made Jeans, and then Denim (yes, in that order)

Since the 1930s, Kojima had been the epicentre of the Japanese textile industry with many weaving and indigo dyeing facilities.

By 1964, one of the town’s garment makers, Maruo Clothing, was on the brink of breaking under fierce competition. Founder Kotaro Ozaki decided to pivot from uniforms into the booming jeans business.

There was only one problem; no one in Japan knew how to make the American kind of denim from heavy duty yarn that would be ring-dyed with indigo. Ozaki needed to import American-made denim, which he got from Canton Mills in Georgia through Ōishi Trading from Tokyo. In his book, Marx argues that Ōishi Trading was, in fact, making the very first Japanese-made jeans, which were labelled with the Canton brand.

Ozaki bought the rights to make Canton jeans west of Hakone in the autumn of 1964, but the denim didn’t arrive in Kojima until February the following year. That’s when Ozaki realised that the Japanese sewing machines couldn’t sew through the heavy denim, so he imported used machinery (including Union Specials) from the US. He bought original ‘made in the US’ thread from Canton Mills, zippers from Talon and rivets from Scowill.

Maruo Clothing’s Canton branded jeans hit the market in April 1965. And they failed catastrophically. Although they were cheaper, the new jeans were outsold 10-to-1 by secondhand jeans.

It wasn’t the price that turned customers away, it was the stiffness of the denim. Basically, the exact same thing that was going on in Europe at the exact same time (which gave François Girbaud the idea to wash the jeans he was selling). Just like the Europeans, the Japanese wanted the soft touch they’d come to know and love from worn and washed secondhand jeans. And like Girbaud, Ozaki’s solution was to wash the jeans before he sold them.

While the washed jeans proved more successful, Ozaki needed a way to target the young trendsetters. That’s when the Big John brand was established for department stores in Tokyo. When the student revolution hit Japan, and—like in the West—made jeans a unifying symbol of rebellion, Big John and other domestically-made Japanese jeans became hugely profitable businesses. But, at this point, their livelihood still depended on imported denim.

In the early 1970s, the Nixon administration imposed trade regulations to protect US production. This wasn’t good news at all for the Japanese jeans makers. That’s when they started making their own denim.

The first commercially successful Japanese denim was made by Kurobo, who used Kaihara’s rope dyeing technique and modern Sulzer wide-looms. Big John used the denim known as KD-8 to make the first fully ‘made in Japan’ jeans. One important detail is that the first Japanese denim wasn’t selvedge—it wasn’t until the late 1970s and early 1980s that they’d figured out how to re-engineer Toyoda looms to weave selvedge denim.

You can read more about blue jeans and denim in Japan in W. David Marx’s fantastic book, Ametora. I simply can’t recommend it enough! Marx has also written a couple of article for Heddels that are recommended reading.

The Early Days of Heritage Fashion in Europe and the US

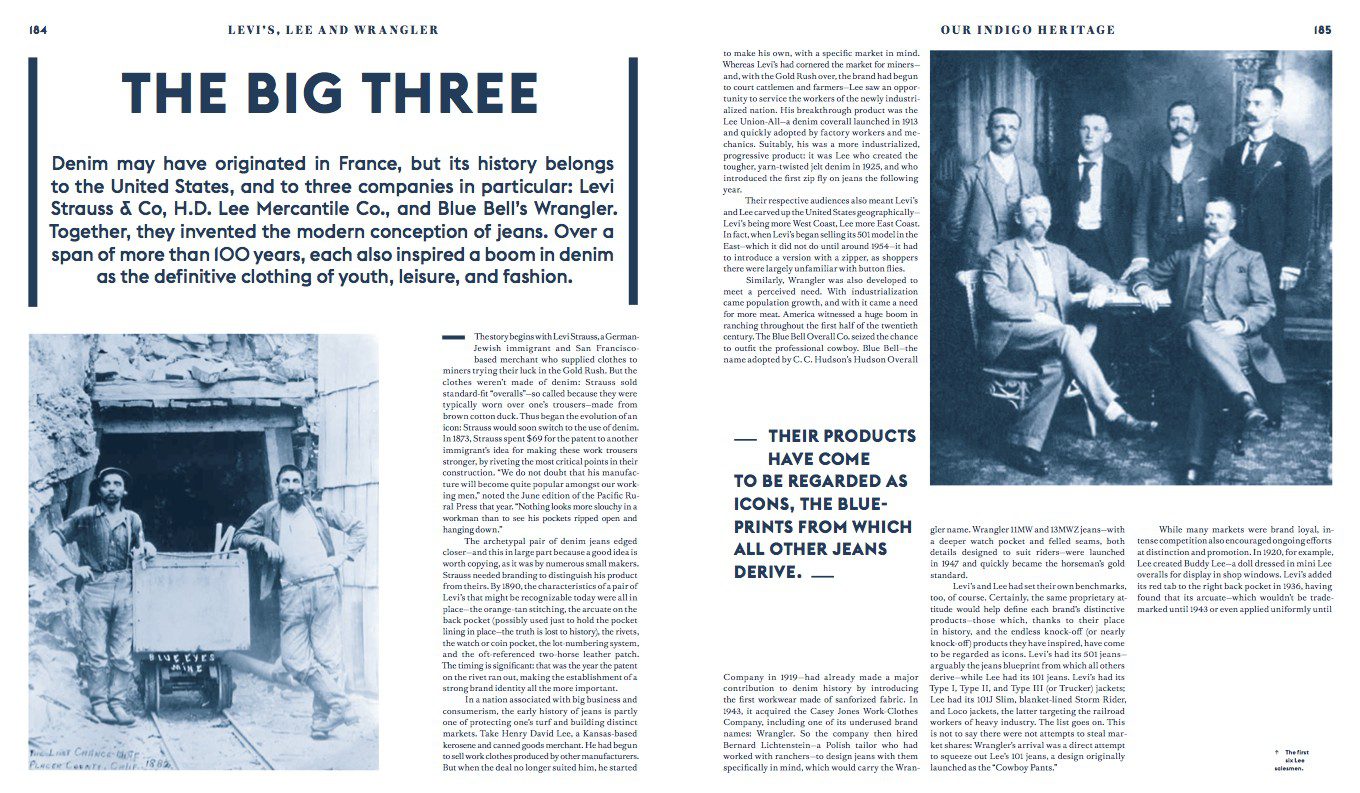

Although initially influenced by European designer jeans brands, the pioneering Japanese brands mainly found inspiration in ‘the Big Three.’ It’s no surprise that replicas of the originals—including the predecessor of Levi’s Vintage Clothing—are products of Japan.

Levi’s Japan launched the first reissue line in 1987. The American headquarters in San Francisco got into the replica business in 1992 with the Capital E line. Capital E jeans featured authentic details such as the Big E red tab, but they were still way too contemporary for denim purists. No one got it right like the Japanese because no one had the same attention to detail and respect for traditions.

Levi’s in Europe was also developing replica products in the early 1990s, when vintage denim was exploding. My fellow Danish denim enthusiast and trend expert, Allan Kruse was working there at the time.

We developed replica products in 1991 and 1992 and launched Big E 501s, Type II and Type III jackets, Orange Tabs and more,” he says in Blue Blooded.

Allan’s team also pushed hard to get non-selvedge raw denim jeans into the red tab collection. It wasn’t a commercial success, but it introduced the concept of raw denim to a wider audience in Europe. It was at this time that European and American denim aficionados discovered some of the very first Japanese heritage brands that came out of the Osaka area.

Evisu and the other Osaka Five—as we westerners have dubbed Studio D’Artisan, Denime, Evisu, Full Count and Warehouse when speaking about them collectively—were making jeans that were exactly like original Levi’s and Lee jeans from the ‘50s and ‘60s.

But the sudden halt of the vintage denim craze in the mid-90s meant that heritage fashion didn’t take off in Europe and the US, yet.

Raw Denim Gains Momentum in Europe and the US in the 2000s

In the early 2000s, the raw denim scene in Europe and the US was influenced by brands like Acne Jeans, A.P.C., Helmut Lang and Dior Homme. Not exactly the kind of brands denimheads of today prefer.

Especially A.P.C. has been a gateway drug into raw denim and fades for many (including myself). The jeans don’t cost a fortune and they fade faster than you can say “made in Macau.”

Dior Homme’s 19 cm jeans—created by Hedi Slimane—were considered the holy grail of raw denim by many back then. While the jeans may seem trivial today, the slim fit—which by 2017 standards is more like a regular fit—was a reaction against the wider cuts of the late-90s. The 19 cm Dior’s became the starting point for slimmer cuts for men’s jeans.

Around 2005, Japanese trends began influencing Europe and the US. Today, pundits sometimes describe heritage fashion as a sign of the global recession of the late-00s. Some have called it as a confrontation with the throwaway culture. Allan Kruse thinks it’s something else.

Heritage fashion started when the West discovered the products that came out of the Japanese penchant for quality and craftsmanship,” he argues in Blue Blooded.

The recession and an intend to throw less away may have accelerated the spread of the trend, though, he acknowledges. But don’t forget that fast fashion is now bigger than ever! In other words, consumers are still buying a lot of ‘throwaway clothes.’

The raw denim movement found an online home on forums like Superfuture and Styleforum. There, a cluster of consumers who valued extreme attention to detail, and were willing to pay a high price for it, met virtually to show fits and fades.

By the late 2000s and through the early 2010s, there was a boom in heritage-oriented brands popping up in Europe and the US. The return to the roots of jeans also fostered a niche of one-man and made-to-measure brands. Eventually, the inevitable happened; heritage went mainstream.

Heritage Fashion Goes Mainstream in the 2010s

While trendsetters and early adopters have been wearing raw denim since the ’80s, the fashion didn’t break into the mainstream until the 2010s. This lead to an exploding demand for cheaper alternatives, which gave birth to a new breed of heritage denim brands: the cut-out-the-middleman kind.

Raw denim has also made it into the world of fast fashion. The best option on the market I’ve seen has to be Uniqlo’s €50 selvedge denim jeans, made from a fabric woven by Kaihara in Japan. I’ve not tested the jeans myself, but they honestly look pretty solid. Not that different from the fabric used for the Levi’s Vintage Clothing 505.

Raw denim has also made it into the world of fast fashion. The best option on the market I’ve seen has to be Uniqlo’s €50 selvedge denim jeans, made from a fabric woven by Kaihara in Japan. I’ve not tested the jeans myself, but they honestly look pretty solid. Not that different from the fabric used for the Levi’s Vintage Clothing 505.

Of course, the way fast fashion companies can sell jeans made from Japanese selvedge denim at prices like that is a little concept called economies of scale. When you book millions of metres of denim, even production in Japanese can get an attractive price point per unit. And, naturally, they’ll sew the jeans in countries where wages are still (alarmingly) low.

While fast fashion raw and selvedge denim jeans will never compare to the pioneering Japanese replica jeans that started the heritage fashion movement, they’re changing the way average Joes look at their jeans. Eventually, some of these guys will become converts and opt for the real deal.

This concludes my analysis of how the Japanese pioneered heritage fashion and changed the history of jeans. I’d love to hear about your experiences with storytelling about the history of jeans. Go ahead and share your thoughts below.

On the Hunt For Raw Selvedge Jeans?

Launched in 2011 by Thomas Stege Bojer as one of the first denim blogs, Denimhunters has become a trusted source of denim knowledge and buying guidance for readers around the world.

Our buying guides help you build a timeless and adaptable wardrobe of carefully crafted items that are made to last. Start your hunt here!

Sources: Ametora and Blue Blooded

Share

Great article … pure denim history .

Thanks

спасибо это отлично.